Executive Summary: Navigating the U.S. Medical Device Regulatory Landscape

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) employs a risk-based classification system for medical devices, categorizing them as Class I, II, or III based on the level of control necessary to ensure their safety and effectiveness. This classification system is foundational, as it directly determines the regulatory pathway required for a device to be legally marketed. Class I devices, which pose the lowest risk, are generally subject only to “general controls” and may be exempt from premarket submission. Class II devices, which are considered moderate-risk, typically require “special controls” in addition to general controls, and most must undergo a Premarket Notification, or 510(k), process. In contrast, high-risk Class III devices, which are often life-sustaining or life-supporting, are subject to the most stringent review, known as Premarket Approval (PMA).

While the 510(k) and PMA pathways serve as the primary mechanisms, the regulatory landscape for medical devices has evolved to accommodate innovation. The De Novo pathway addresses a crucial gap for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices that do not have a legally marketed predicate device to which they can be compared. This pathway allows for a risk-based reclassification of such devices into Class I or II. The selection of the appropriate premarket submission pathway is not merely an administrative exercise but a critical business and compliance decision that profoundly impacts a device’s time-to-market, development costs, and overall commercial viability. A clear understanding of these three pathways—510(k) for clearance, PMA for approval, and De Novo for classification—is essential for any organization seeking to navigate the U.S. market effectively.

Section 1: The Foundational Framework of FDA Medical Device Regulation

1.1. The Risk-Based Classification System

The FDA’s classification of medical devices is a direct function of risk, with regulatory oversight increasing proportionally from Class I to Class III. This system is codified in the Code of Federal Regulations, and the device classification regulation defines the regulatory requirements for each general device type.

Class I (Low-Risk): These devices are considered low-risk and are subject only to “general controls”. General controls are a set of baseline requirements that apply to all three device classes, including provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act. These controls prevent adulterated and misbranded devices and require manufacturers to register their establishments, list their devices, and adhere to quality system regulations and adverse event reporting. Examples of Class I devices include adhesive bandages, manual stethoscopes, and surgical scalpels. A majority of Class I devices are exempt from the need for a premarket submission.

Class II (Moderate-Risk): Devices in this class are deemed to have a moderate risk to the patient or user. In addition to general controls, they are subject to “special controls” to provide a reasonable assurance of their safety and effectiveness. Special controls are often device-specific and can include performance standards, post-market surveillance, patient registries, and special labeling requirements. Common examples of Class II devices include powered wheelchairs, surgical drapes, and X-ray machines. The majority of Class II devices require a 510(k) premarket notification before they can be marketed.

Class III (High-Risk): This is the highest-risk class, reserved for devices that are life-supporting, life-sustaining, or of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health, or that may pose a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury. Because general and special controls are considered insufficient to provide a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for these devices, they must undergo the rigorous Premarket Approval (PMA) process. Examples of Class III devices include pacemakers, heart valves, and implantable defibrillators.

1.2. Strategic Pathway Selection and Preliminary Steps

The most important strategic decision for a manufacturer is the accurate classification of their device, as this choice cascades to every subsequent regulatory and business decision. The device’s intended use and technological characteristics directly determine its inherent risk level, which in turn dictates the required regulatory pathway. The FDA’s classification database is a critical tool for this initial determination, allowing manufacturers to search for similar devices and their corresponding product codes and regulatory requirements.

For devices with a novel intended use or uncertain classification, a strategic preliminary step is to submit a 513(g) Request for Information. This submission provides a formal mechanism to seek a ruling from the FDA on a device’s classification and the regulatory requirements that would apply. While a 513(g) does not grant marketing authorization, it can provide crucial clarity within 60 days, helping manufacturers avoid costly regulatory delays and expenses that could arise from pursuing an incorrect submission pathway.

A deeper examination of the FDA’s engagement model reveals a trend of encouraging early, proactive dialogue with manufacturers. The FDA offers “pre-submission meetings” and other feedback mechanisms, which are explicitly mentioned in the context of PMA and De Novo submissions. This shift from a reactive, submission-and-review model to a more collaborative partnership suggests that the agency values transparency and aims to provide guidance early in the development cycle. By engaging with the FDA before a formal submission, companies can align their regulatory strategy with the agency’s expectations, thereby reducing the risk of a Refuse to Accept (RTA) decision or an extensive review period. This proactive approach can significantly streamline the path to market.

Section 2: The Premarket Notification (510(k)) Pathway

2.1. Purpose and Strategic Applicability

The 510(k) pathway is a premarket notification process for Class II and some Class I devices that are not exempt from premarket submission. Its central purpose is to demonstrate that a new medical device is “substantially equivalent” (SE) to a legally marketed predicate device. A predicate device is one that was legally marketed prior to May 28, 1976 (a “preamendments device”), has been reclassified from Class III to a lower class, or was found substantially equivalent through a previous 510(k) clearance.

The concept of substantial equivalence is crucial. A device is considered SE if it has the same intended use and the same or similar technological characteristics as a predicate device, and if any differences in technological characteristics do not raise new questions of safety or effectiveness. The 510(k) process is a “clearance” mechanism, not an “approval” process. This distinction is critical from a marketing perspective, as manufacturers of 510(k)-cleared devices cannot advertise them as “FDA-approved”.

2.2. Key Components of a 510(k) Submission

The FDA provides the necessary forms and checklists for a 510(k) submission on its official website. As per

21 CFR 807.92, a 510(k) summary must be in sufficient detail to provide a clear understanding of the basis for the substantial equivalence determination.

Predicate Device Identification: The most crucial first step in preparing a 510(k) is identifying a suitable predicate device. The device being submitted for clearance must be essentially identical to the predicate in terms of its intended use, indications for use, and technology. The FDA’s searchable database of releasable 510(k)s is an essential resource for this purpose.

Device Description and Intended Use: The submission must include a detailed description of the device, explaining how it functions, the scientific concepts behind its operation, and its significant physical and performance characteristics. A clear statement of the device’s intended use, including the diseases or conditions it will diagnose or treat, is also required. If the indications for use differ from the predicate, the submission must explain why the differences are not critical to the device’s use.

Performance Data: To support the claim of substantial equivalence, the submission must include performance data. This generally consists of non-clinical data from laboratory testing, such as bench testing, software verification and validation, and risk analysis. While human clinical data is not generally required for a 510(k), it may be necessary if the device’s technological differences from the predicate raise new questions of safety or effectiveness.

Labeling and Quality System: Proposed labeling is a mandatory component. Additionally, the submission must demonstrate compliance with the Quality System (QS) regulation, specifically 21 CFR Part 820. The design control process, as outlined in the QS regulation, is a key consideration, and documentation such as software architecture diagrams and risk management plans are often required.

2.3. The 510(k) Review Process and Timeline

The FDA’s target for reviewing a 510(k) submission is 90 days, but the overall process can take much longer. The timeline begins with the FDA receiving the application and issuing an acknowledgement or hold letter within 7 days. An Acceptance Review is then conducted by day 15 to determine if the submission is ready for a substantive review or if it will be placed on an RTA (Refuse to Accept) hold. The FDA will conduct a substantive review by day 60, after which it may request additional information. The final decision, known as the MDUFA Decision, is targeted for day 90.

An analysis of recent trends reveals that a significant percentage of 510(k) applications are initially not accepted for review due to common administrative errors, such as incorrect templates and disorganized documentation. This highlights a crucial dynamic: the success of a 510(k) submission depends not only on a device’s safety and performance but also on the meticulous organization and administrative precision of the application itself. The FDA’s strict administrative requirements mean that a failure to adhere to them can lead to a formal RTA decision, causing regulatory delays and increased costs. This demonstrates that for a manufacturer, a successful submission is a matter of both scientific rigor and administrative discipline.

2.4. Example: A Blood Glucose Monitoring System

A concrete example of the 510(k) process in action is the submission for the iHealth Wireless Gluco-Monitoring System. The applicant, Andon Health Co., Ltd., submitted a 510(k) to demonstrate that its new device was substantially equivalent to its own previously cleared device, the

iHealth BG5 Wireless Smart Glucose Monitoring System.

The submission summary includes a detailed comparison of the new device and its predicate across key technological characteristics, such as:

- Detection Method: Amperometry.

- Enzyme: Glucose Oxidase.

- Sample Source: Capillary whole blood from alternative sites and the fingertip.

- Test Time: 5 seconds.

- Measurement Range: 20mg/dL-600mg/dL.

This side-by-side comparison provided the necessary evidence to support the claim of substantial equivalence. The FDA reviewed this data, concluded that the new device had the same intended use and did not raise any new questions of safety or effectiveness, and issued a substantial equivalence determination, thereby clearing the device for market.

Reference : 510(k) Summary – accessdata.fda.gov, accessed August 24, 2025, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/K153278.pdf

2.5. Official Links

- Premarket Notification 510(k):

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions-selecting-and-preparing-correct-submission/premarket-notification-510k - 510(k) Database Search: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm

- 510(k) Forms ; https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-notification-510k/510k-forms

Section 3: The Premarket Approval (PMA) Pathway

3.1. Purpose and Strategic Applicability

PMA is the most demanding and comprehensive pathway for medical device marketing authorization in the United States. It is a scientific and regulatory review process required for all Class III devices to ensure their safety and effectiveness. A PMA is also required for devices that are found to be “not substantially equivalent” (NSE) through the 510(k) process and are not eligible for a De Novo request.

The PMA process involves higher standards than the 510(k) and necessitates a far more detailed and comprehensive body of evidence. Unlike a 510(k) clearance, a successful PMA results in an “approval,” which is a private license for the applicant to market a specific medical device.

3.2. Key Components of a PMA Submission

A PMA application does not have a preprinted form but must include a detailed set of required elements, as specified in 21 CFR Part 814.

- Comprehensive Device Description: This section must provide a complete and detailed description of the device, including its functional components, its underlying scientific concepts, its physical and performance characteristics, and a description of the manufacturing process if it is relevant to understanding the device.

- Nonclinical Laboratory Studies: This technical section requires extensive data from laboratory and animal tests to demonstrate safety. Examples include studies on microbiology, toxicology, biocompatibility, stress, wear, and shelf life. The submission must affirm that these studies complied with

21 CFR 58 (Good Laboratory Practice) or provide a justification for any noncompliance.

- Clinical Investigations: This is the most data-intensive part of the submission, requiring robust scientific evidence to prove both safety and effectiveness. The PMA must include detailed clinical protocols, data from all subjects, adverse reaction reports, and statistical analysis results. The submission must also confirm that the clinical investigations complied with relevant regulations, including

21 CFR 50 (Informed Consent), 21 CFR 56 (Institutional Review Board), and 21 CFR 812 (Investigational Device Exemptions).

- Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data (SSED): The SSED is a public-facing, 10-15 page summary that provides a general understanding of the data in the application, including the results and conclusions from both the nonclinical and clinical studies.

3.3. The PMA Review Process and Timeline

The PMA review is a multi-stage process with a target review timeline of 180 days from the date of filing.

- Filing: Within 45 days of receipt, the FDA determines if the application is sufficiently complete to be “filed,” which triggers the start of the in-depth review. An application may be refused for filing if it is incomplete or unclear.

- In-Depth Substantive Review: Following filing, the FDA conducts a comprehensive review of the application’s scientific and technical sections. This is the core of the review, during which the FDA may issue deficiency letters requesting additional information.

- Panel Review: The FDA may refer a PMA, particularly for a “first-of-a-kind” device, to an outside advisory panel of experts for review and recommendation.

- Facility Inspection: Before a PMA can be approved, the FDA typically conducts a facility inspection to confirm compliance with Quality System Regulation (21 CFR 820).

A strategic evolution in the PMA process can be observed in the development of “Modular PMA” and “Product Development Protocol (PDP)” pathways. The traditional PMA’s monolithic nature, with all volumes of material submitted at once, can expose a manufacturer to a high risk of a “not approvable” decision after significant investment in development and clinical trials. To mitigate this, the Modular PMA allows manufacturers to submit a PMA in well-delineated components (modules) as they are completed, enabling the FDA to provide timely feedback throughout the review process. The PDP, an even more collaborative approach, establishes a formal agreement with the FDA on the data and milestones needed to demonstrate safety and effectiveness, effectively merging the development and regulatory processes. These alternative methods were created to reduce the risks inherent in the traditional PMA process and potentially accelerate the time to market.

3.4. Example: A Focused Ultrasound System

The PMA for the ExAblate Focused Ultrasound System provides a clear example of the data requirements for a Class III device.

- Nonclinical Data: The SSED for this PMA details the device’s compliance with a variety of standards, including

IEC 60601-lfor electrical safety andEN 60601-1-2for EMC safety. It also references biocompatibility testing on a patient gel pad, with a note referencing a previous 510(k) clearance, demonstrating how data can be leveraged across submissions. - Clinical Data: The SSED describes a prospective, single-arm clinical study designed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the device. This highlights the necessity of human clinical data to support a PMA, as the FDA requires evidence that a device’s benefits to health outweigh its risks for the target population.

- Reference : 510(k) Summary – accessdata.fda.gov, accessed August 24, 2025, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/K153278.pdf

3.5. Official Links

- PMA Official Page:

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma - PMA Database Search: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pmasimplesearch.cfm

- PMA Regulations: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-regulations

Section 4: The De Novo Classification Request Pathway

4.1. Purpose and Strategic Applicability

The De Novo pathway is a premarket submission mechanism that provides a route to market for novel medical devices that are classified as low to moderate risk but lack a legally marketed predicate device. Without this pathway, such devices would be automatically classified as Class III and would be required to undergo the arduous PMA process, a disproportionate regulatory burden for a low-risk product.

There are two primary submission options for a De Novo request. The first is to submit a De Novo request directly when a manufacturer determines that no legally marketed predicate device exists. The second is to submit a 510(k) and, if it receives a “not substantially equivalent” (NSE) determination from the FDA, to then submit a De Novo request within 30 days of the NSE decision.

4.2. Key Components of a De Novo Request

The official requirements for a De Novo request are detailed in the Code of Federal Regulations, specifically 21 CFR 860.230.

- Justification for De Novo Eligibility: The submission must provide a complete description of the searches performed to confirm that no legally marketed predicate device of the same type exists. It must also include a list of potentially similar classification regulations and a rationale explaining how the new device is different from those identified.

- Summary of Risks and Mitigations: The request must include a summary of all probable health risks associated with the device and a detailed description of the proposed mitigation measures. This includes the general controls and, if a Class II classification is recommended, the proposed special controls for each identified risk.

- Proposed Special Controls: If the device is recommended for Class II, the submission must include a draft proposal for the new special controls and a description of how they would provide a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for this novel device type.

- Classification Recommendation: The manufacturer must recommend a classification (Class I or II) and provide a justification for why general controls alone, or general and special controls, are sufficient to ensure the device’s safety and effectiveness.

4.3. The De Novo Review Process and Timeline

The De Novo review process includes an initial Refuse to Accept (RTA) screening to check for administrative completeness, similar to the 510(k) and PMA pathways. Once accepted, the FDA’s target review period is 150 days. However, a direct examination of recent data reveals that the average approval wait time can be significantly longer, reflecting the complexity of assessing a novel technology without a predicate.

The De Novo pathway is a key enabler of innovation. The absence of a predicate can lead to an automatic Class III designation, which would force a low-risk device into a high-cost, high-time PMA process that is not commensurate with its risk level. The De Novo pathway circumvents this by establishing a new classification and regulatory framework tailored to the device’s actual risk, thereby fostering the development of new technologies that do not fit into existing categories. The successful classification of a device through this pathway is particularly valuable, as it creates a new product code and regulation, allowing the device to serve as a predicate for future 510(k) submissions of similar devices.

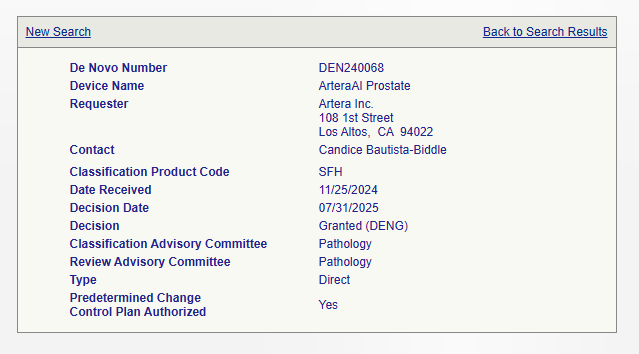

4.4. Example: The ArteraAI Prostate Tool

The De Novo authorization for the ArteraAI Prostate tool serves as a powerful illustration of this pathway’s strategic value, particularly for emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI). The ArteraAI tool is a novel, AI-powered diagnostic and risk stratification tool that analyzes a patient’s biopsy images and clinical data to predict long-term outcomes for prostate cancer.

The tool’s novelty—being the “first and only AI-powered tool” for this specific purpose—meant that no suitable predicate device existed in the market. This lack of a predicate made it a prime candidate for the De Novo pathway. The company’s submission provided clinical data, validated in Phase 3 trials, to demonstrate the device’s effectiveness. The FDA’s decision to grant the De Novo request not only authorized the device for marketing but also established a “new product code category for future AI-powered digital pathology risk-stratification tools”. This creates a clear regulatory path for similar devices that may be developed in the future, thereby leveraging the initial investment in the De Novo process to benefit a wider field of innovation.

Reference : https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/denovo.cfm?id=DEN240068

4.5. Official Links

- De Novo Official Page:

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions-selecting-and-preparing-correct-submission/de-novo-classification-request - De Novo Database Search: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/denovo.cfm

- eCFR De Novo Regulations: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-860/subpart-D

Section 5: Strategic Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Pathways

A side-by-side comparison of the 510(k), PMA, and De Novo pathways is essential for understanding their distinct roles and strategic implications.

| 510(k) (Premarket Notification) | PMA (Premarket Approval) | De Novo (Classification Request) | |

| Purpose | To demonstrate “Substantial Equivalence” to a predicate device | To ensure a device is safe and effective for its intended use | To create a new regulatory classification for a novel, low-to-moderate-risk device |

| Risk Class | Primarily Class II | Class III | Class I or Class II |

| Required Evidence | Comparison to a predicate device; typically non-clinical data | Extensive scientific evidence, including detailed non-clinical and clinical data | Justification for lack of a predicate and evidence to demonstrate safety and effectiveness via proposed controls |

| Timeline (FDA Target) | 90 days | 180 days | 150 days (longer average) |

| Outcome | “Cleared” | “Approved” | “Granted Classification Order” |

The choice between these pathways represents the most significant regulatory decision a manufacturer will make. The existence of multiple pathways for different risk profiles and technological characteristics showcases the FDA’s dynamic approach to regulation. For example, while many high-tech, complex devices might seem to be Class III candidates, a device like a robotic surgical system is often regulated as a Class II device requiring a 510(k). This is because it can be shown to be “substantially equivalent” to conventional surgical tools, and any technological differences do not raise new questions of safety or effectiveness. This demonstrates that even for a highly advanced device, a valid predicate can prevent the need for the more burdensome PMA pathway.

For devices with no clear predicate, manufacturers have a strategic choice. They can either submit a 510(k) first to test the “not substantially equivalent” (NSE) argument and then pivot to a De Novo request within 30 days of the NSE decision, or they can submit a De Novo request directly. A pre-submission meeting with the FDA is an invaluable tool for gaining clarity on the appropriate path and required data, thereby reducing regulatory risk and optimizing the strategic approach.

Section 6: Conclusion and Future Outlook

The FDA’s regulatory framework for medical devices is a sophisticated, risk-based system designed to ensure safety and effectiveness while fostering innovation. The 510(k), PMA, and De Novo pathways are not arbitrary hurdles but carefully crafted mechanisms that align the level of regulatory scrutiny with a device’s inherent risk. The analysis of these pathways reveals that the most critical strategic decision a manufacturer will make is the accurate classification of their device and the selection of the correct premarket pathway. This initial determination dictates the required data, timeline, and associated costs for the entire development process.

The FDA’s evolving regulatory landscape, marked by a greater emphasis on early, pre-submission dialogue and the establishment of new pathways like De Novo, indicates a strategic shift. The agency is actively working to streamline the process, reduce risk for manufacturers, and adapt to the rapid pace of technological advancement, particularly with the proliferation of software as a medical device (SaMD) and AI-enabled devices. The increasing reliance on the De Novo pathway to create new product codes and regulatory categories for these technologies highlights its role as a key enabler of future innovation. Understanding and strategically navigating these pathways is therefore not just a matter of compliance but a fundamental component of a successful business strategy in the medical device industry.